What did ancient Greek and Roman writers say about Chandragupta Maurya (Sandracottus)?

The Mauryan empire of ancient India is an epochal moment in Indian history. Founded by Chandragupta Maurya after the overthrow of the Nanda dynasty ruler Dhana Nanda (Augrasainya), the empire reached its zenith under his grandson Ashoka (Ashoka the Great), spanning from Afghanistan, to the eastern borders of India, and all the way to the South to the modern state of Karnataka. Taken together, the Mauryan empire’s geographical coverage at Chandragupta’s time was greater than the combined approximate size of modern Iraq, Iran, Iraq, Syria, Jordan, Israel, Lebanon, Afghanistan, Greece, Macedonia. And it became even larger during his grandson’s time.

But how much do we know about this first emperor? The reality is that not a lot. Like many famous people from the ancient world, details about their lives are lost to history, and we are left forming an idea by cobbling bits and pieces from works often written hundreds of years after. For example, take the famous Cleopatra, so well-known from movies, documentaries, and books (including /mine). Everything we know about her comes from Roman sources written hundreds of years after her death. She left behind not a single full-sized statue or portrait of her unearthed in Egypt, and in fact, we do not even know who her mother was. Not a single papyrus documenting her rule or reign has been found. A similar situation applies to Chandragupta Maurya. There is not a single credible archaeological evidence of this emperor by way of palaces, statues, or rock edicts, so how do we know about him?

We are aware of his existence through two principal sources: (1) references in ancient Greek and Roman sources, and (2) mentions in Indian Jain and Buddhist literature. However, we should remember that the earliest references to this king come from a source nearly 300 years after his time, referring to older sources that are now lost.

On the internet, you will often find speculative information about Chandragupta based on questionable sources and sometimes, simply made up (for e.g., his Greek wife’s name, which, by the way, is never mentioned anywhere in the historical sources). In this post, I present the actual references to him, and from these, we can draw the best possible summary of what we learn.

The definitive work about Chandragupta and India would have been Indica, written by Megasthenes, the ambassador to the Mauryan court, sent by Seleucus Nicator after his treaty with Chandragupta Maurya somewhere around 310 B.C. However, the original work has been lost to history; however, later writers referenced this book, so we get little glimpses of what Megasthenes may have written (though, curiously, Strabo, a Greek writer from early 1st CE, says Megasthenes is a liar and unreliable because he made fantastical claims about India, and we will cover that in this blog later).

There are six principal sources on ancient India:

-

Strabo - A Greek geographer, philosopher, and historian of the 1st century BC; his principal work, “Geographica,” provided invaluable insights into the world during his time.

-

Plutarch - A Greek biographer and essayist from the 1st century AD; his “Parallel Lives” chronicled the lives of notable Greeks and Romans, juxtaposing their deeds and characters.

-

Pliny the Elder - A Roman author, naturalist, and naval commander of the 1st century AD; his encyclopedic work “Natural History” is an authoritative reference on ancient knowledge about the natural world.

-

Arrian - A Roman historian and military commander of the 2nd century AD; best known for “Anabasis of Alexander,” a detailed account of Alexander the Great’s campaigns.

-

Justin - A Latin historian from the 2nd or 3rd century AD; while many of his works have been lost, his surviving “Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus” provides a condensed version of an earlier history of the world.

-

Orosius - An early Christian historian from the 4th and 5th centuries AD; in his “Seven Books of History Against the Pagans,” he aimed to refute the claim that the decline of the Roman Empire was due to its acceptance of Christianity.

Note that while many write that Pliny the Elder mentions Chandragupta, he actually does not mention the king by any name. Instead, he only speaks of the powerful “Prasii” and their capital Palibothra (Pataliputra).

So, here are excerpts of what the above writers say about Chandragupta. His Latinized name is “Sandrocottus”/ “Sandracottus” / “Androcottus.” Note that there has been some debate that Sandrocottus actually refers to “Samudragupta” (a different ruler) rather than Chandragupta, but the general consensus and matching of timelines suggest that it is very likely Chandragupta.

Strabo

Writing sometime between 40 BC and 20 AD, Strabo’s work on the geographies of various parts of the world also mentions India. In that, here is what he says about Chandragupta.

“…formerly belonged to the Persians. Alexander took these away from the Arians and established settlements of his own, but Seleucus Nicator gave them to Sandrocottus, upon terms of intermarriage and of receiving in exchange five hundred elephants…”

So, all Strabo says is that Seleucus ceded some territories to Sandrocottus (Arians, referencing to Arachosia, which would be parts of modern Pakistan and Afghanistan), received 500 elephants, and settled terms of intermarriage. Note that he does not say Seleucus gave his daughter to Sandrocottus—so intermarriage might simply mean both the kings agreeing to the legality of marriage between the Greek settlers and Indians, which the Indians may have prohibited previously.

Strabo’s account, the earliest we have mentioning Sandrocottus, is almost 300 years after the king’s time. But Strabo says he referred to Megasthenes, though he says: “However, all who have written about India have proved themselves, for the most part, fabricators, but pre-eminently so Deïmachus; the next in order is Megasthenes…” I find this very amusing, and share Strabo’s disdain, because if these men really wrote things like: “men that sleep in their ears,” and the “men without mouths,” and “men without noses”; and about “men with one eye,” “men with long legs,” “men with fingers turned backward”; and they revived, also, the Homeric story of the battle between the cranes and the “pygmies,” who, they say, were three spans tall. These men also tell about the ants that mine gold and Pans with wedge-shaped heads; and about snakes that swallow oxen and stags…” then it does put to question the quality of their work and the reasons behind such fabrication—unfortunately, there is no way to verify because the original works have been lost.

(Note: Deimachus served as an ambassador to Bindusara, the son of Chandragupta Maurya. Strabo misidentifies him as Allitrochades, the son of Sandrocottus. “Allitrochades” is a Latinized rendition of Amitraghāta, another name for Bindusara. This suggests that Strabo likely made an error in transcription, possibly mistaking Ammitrochades for Allitrochades.)

Continuing with Plutarch, writing about four centuries after the era of Chandragupta.

Plutarch

”… For they were told that the kings of the Ganderites and Praesii were awaiting them with eighty thousand horsemen, two hundred thousand footmen, eight thousand chariots, and six thousand fighting elephants. And there was no boasting in these reports. For Androcottus, who reigned there not long afterwards, made a present to Seleucus of five hundred elephants, and with an army of six hundred thousand men overran and subdued all India.”

The Ganderites might be synonymous with the “Gangaridae,” a term likely translating to Ganga-Hriday (heart of the Ganges), which possibly refers to the kingdom of Kalinga. Meanwhile, Praesii might pertain to inhabitants near Palibothra. Plutarch refers to Chandragupta as “Androcottus” instead of “Sandrocottus.”

Plutarch’s narrative underscores Chandragupta’s gift of elephants to Seleucus (a detail similarly noted by Strabo). Yet, there’s no account of any conflict or matrimonial alliances between the two empires. Notably, none of the authors mentioned the “Maurya” dynasty or a matrimonial alliance involving a Greek princess.

Pliny the Elder

An influential figure from the 1st century AD, Pliny the Elder was a prodigious writer. Interesting fact: he met his demise observing the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, which engulfed Pompeii and Herculaneum.

In his writings, while Pliny frequently references Megasthenes and Deimachus regarding India, he notably omits specific references to Sandrocottus. The fantastical descriptions of India in his echo Strabo’s criticisms.

Arrian

Arrian’s Anabasis of Alexander stands as a pivotal source. It offers an extensive account of Alexander’s Indian expedition. Arrian relied on significant sources from the time of the invasion, prominently Ptolemy and Aristobulus. He wrote about four centuries after Alexander.

Unfortunately Arrian says nothing that is of interest. All he states is that Megasthenes met Sandracottus who was the greatest Indian king. And later, he talks of how many kings were between Dionysus (Greek deity) and Sandracottus.

Justin

About half a millennium after Chandragupta, Justin presents one of the most comprehensive records on Chandragupta.

Source: Book XV here

“After the division of the Macedonian empire among the followers of Alexander, he carried on several wars in the east. He first took Babylon, and then, his strength being increased by this success, subdued the Bactrians. He next made an expedition into India, which, after the death of Alexander, had shaken, as it were, the yoke of servitude from its neck, and put his governors to death. The author of this liberation was Sandrocottus, who afterwards however, turned their semblance of liberty into slavery; for, making himself king, he oppressed the people whom he had delivered from a foreign power, with a cruel tyranny. This man was of mean origin, but was stimulated to aspire to regal power by supernatural encouragement; for, having offended Alexander by his boldness of speech, and orders being given to kill him, he saved himself by swiftness of foot; and while he was lying asleep after his fatigue, a lion of great size having come up to him, licked off with his tongue the sweat that was running from him, and after gently waking him, left him. Being first prompted by this prodigy to conceive hopes or royal dignity, he drew together a band of robbers, and solicited the Indians to support his new sovereignty. Some time after, as he was going to war with the generals of Alexander, a wild elephant of great bulk presented itself before him of its own accord, and, as if tamed down to gentleness, took him on its back, and became his guide in the war, and conspicuous in fields of battle. Sandrocottus, having thus acquired a throne, was in possession of India, when Seleucus was laying the foundations of his future greatness; who, after making a league with him, and settling his affairs in the east, proceeded to join in the war against Antigonus. As soon as the forces, therefore, of all the confederates were united, a battle was fought, in which Antigonus was slain, and his son Demetrius put to flight.”

Justin says more than most others, possibly drawing from older sources. According to him, the Indians, presumably under Chandragupta, had killed off Alexander’s prefects and got themselves freedom. But apparently Chandragupta treated them cruelly. And then, Seleucus it seems “made a league with him” (i.e., presumably came to terms) and settled his affairs in the east, though he makes no mention of the specific terms or how they were settled. But what we can infer is that the Indians had killed or deposed the Greek governors left behind by Alexander, and that Seleucus’s attempts in the east, whatever they were, were not fruitful.

He is also the only source who suggests that he “offended” Alexander (and therefore implying he met Alexander at some point, years before his ascension to throne, when he would still likely be a boy if we go by the general timelines of his rule). In my novel The Atlantis Papyrus I play with this concept briefly. We do not know where Justin got the rest of the narrative (supernatural elements and so on)—presumably Megasthenes, if we go by Strabo’s account that Megasthenes “made up a bunch of things.”

Orosius

Around 410 A.D., about 700 years after Chandragupta’s time, the early Christian historian and theologian Orosius wrote:

“Next he made a journey to India, whose people, after the death of Alexander, had killed his prefects. Rising in revolt and seeking to win their freedom under the leadership of a certain Androcottus, they had thrown off his yoke from their necks. Later Androcottus, acting with great cruelty toward the citizens whom he had saved from foreign domination, oppressed them with slavery. Seleucus, although he had waged bitter wars against Androcottus, finally withdrew from the country after concluding a pact with him and arranging the terms by which the latter should hold the kingdom.”

Orosius’ account seems to mirror Justin’s writings closely. It’s probable that Orosius drew inspiration from Justin, as he doesn’t provide any novel insights.

Summary

From the records, what do we conclusively discern?

- Post-Alexander, Chandragupta founded a vast empire in India.

- He engaged with Seleucus Nicator, resulting in territorial negotiations and a potential exchange of elephants.

- There isn’t any concrete evidence from these sources about him wedding a Greek princess. Most claims on this matter stem from misinterpretations or references from secondary or later sources.

- Justin’s account, while being theatrical, sheds light on Chandragupta’s early days and ascent to power.

- Chandragupta’s empire was expansive and held in high esteem.

That is the gist of it. There are no specific details of battles, where they fought, or even if they fought at all. There’s no clarity on whether Seleucus gave his daughter, niece, relative, or a friend’s aunt in marriage, let alone her name, and which specific territories he ceded (except possibly Arachosia, as mentioned by Strabo). Much of this has been inferred, either by considering the larger geopolitics of the time or by the actions and evidence of rulers who succeeded Chandragupta.

For example, why do we think Seleucus returned some of his territories to Chandragupta? Because we find Ashokan rock edicts in modern Afghanistan (Seleucid territory), and Ashoka was Chandragupta’s grandson. Ashoka never mentions wars on that front, and it appears those regions, supported by Buddhist evidence, belonged to the Mauryas. We can, therefore, reasonably conclude that the Greek writers’ mention of “settlement of affairs” and Chandragupta’s gift of five hundred elephants (a tactical advantage in Seleucus’ wars in the west) were possibly due to Seleucus’ setbacks in the east. Chandragupta might have used this to not only gain territory but also to ensure that Seleucus could happily redirect his attention and resources to the west, by gifting him the elephants.

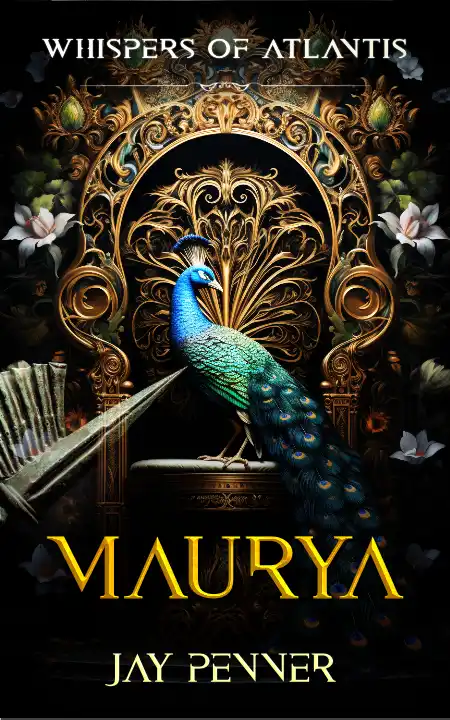

So, that is the story of Sandracottus or Chandragupta. If you’re interested in an adventure set in that time, consider Maurya!

4.5/5 from 4000+ ratings (overall). Grab a thriller from Jay.

🔥 Deon and Eurydice return in this thrilling new adventure in ancient India!

An amazing 4.9/5 🌟 on Goodreads!

309 B.C. India.

Who’s lying?

It has been nearly fifteen years since Alexander the Great’s death, and his kingdom, from Macedonia to the borders of India, has been torn to pieces by his rapacious and ambitious generals. Seleucus Nicator reigns in Babylon, presiding over the eastern empire from Syria to the Indus River.

But no expanse of land is enough for the insatiable ego of a man who seeks glory by accomplishing what his deified King once could not—conquering the vast and wealthy India, where a powerful new emperor, guided by a cunning and brilliant mentor, poses a threat to Seleucus’ ambitions.

Now, Deon, with his prodigious memory, and Eurydice, with her linguistic prowess, are back, assisting Seleucus in a diabolical new mission into the heart of the unknown. The two are about to plunge into a dangerous and unfamiliar world, where wit is as much a weapon as a sword, and where one miscalculation can lead not only to their terrible deaths but end the entire Seleucid empire.

Deon and Eurydice return once again in this sixth book of the Whispers of Atlantis anthology that can also be enjoyed as a standalone.

Jay Penner’s highly-rated books regularly feature Amazon’s category bestseller lists. Try his Spartacus, Cleopatra, Whispers of Atlantis or Dark Shadows books. Reach out to him or subscribe to his popular newsletter.